Small Business Administration Case Study

Contributing Authors

- Brianna Bischofberger: UX Designer

- Noah Brod: SBA Stakeholder/Project Sponsor

- Benjamin Elias: Excel/Google Site Guru

- Vincent La: Data Scientist/Project Technical Lead

- Mike Mathews: Data Pipeline Engineer

- Kenny Nieh: Product Designer

Project Context

| Product Name: | SBAapp (Small Business Administration application) |

|---|---|

| Team Name: | C4SF-SBA (Code for San Francisco - Small Business Admin) |

| Timeframe: | ~11 months |

| Team members: |

|

| Github: | https://github.com/sfbrigade/datasci-sba |

| Webpage: | https://sites.google.com/site/cfasbadash/data-map |

| MVP Prototype: | https://ec2-54-175-133-20.compute-1.amazonaws.com/app/ |

Introduction

The Small Business Administration is a federal agency whose mission is to help Americans start, grow and build businesses. The SBA provides tools and resources critical to the success of America’s 28 million small businesses. These businesses account for more than 56 million jobs and create two out of three net new jobs in the U.S. each year. Since starting as an agency in 1953 the SBA has helped millions of entrepreneurs.

One of the ways that the SBA assists business owners is by helping to address financing gaps for business owners. SBA partners with lenders across the country to provide business owners reasonable financing options with terms that are friendly to business owners. Across the country the SBA also has local offices that help to promote the programs, guide business owners to resources, and encourage outside partners to help small businesses.

In October of 2016 the SBA released detailed data on two of the major financing programs for small businesses that they administer. The data included over 1.5 million loan entries with detailed loan information. With the release of the data, local SBA offices have been able to communicate the impact of the SBA programs at a more local, granular level - using this detailed data rather than regional aggregates. Prior to the release of this data into the public interested parties had to submit a FOIA request and wait for months in order to get basic information about how SBA programs were benefiting businesses in their local area. Local SBA offices were limited to providing very high level summary data that was often not relevant or detailed enough to communicate the importance of the SBA programs at a local level. However, even after the lending data was released into the public it was still taking a significant amount of time to pull up reports and communicate information to partners. Furthermore, the now public data was still being used in a passive way by local offices. If a party asked for data, SBA offices were better able to accommodate them, but the local offices were not integrating the public data into their decision-making, communications, or strategies for building out new partnerships and promoting the SBA lending programs.

Following the release of the SBA’s lending data programs, Noah Brod, an economic Development Specialist with the SBA in San Francisco, reached out to the SF Brigade at Code for America with three different project ideas:

- How might the SBA more efficiently identify and highlight successful business owners that have benefited from SBA programs?

- How might the newly released data be used to identify areas in our local district that are under or over participating in our programs?

- How might we better facilitate connections between entrepreneurs and the non-profits that serve them?

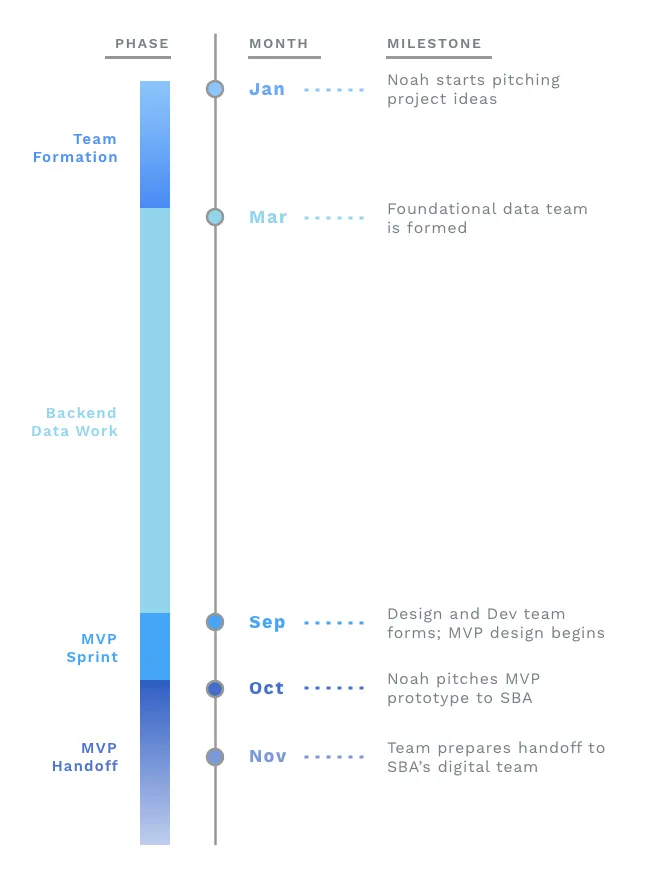

Phase 1: Noah starts pitching Timeframe: January to March

Noah spent 2 hours once a week over two months at the SF brigade refining these problem statements and recruiting volunteers to explore potential solutions and generate small working prototypes. Being persistent in repeatedly pitching the project each week and narrowing the scope of the project as he onboarded new members was key as it allowed the team to slowly grow and start to work more independently over time and recruit their own volunteers for more specific needs as they arose. An early win was when SF brigade volunteer Vince La joined the team. Vince brought a set of project management skills to the group that kept all of the volunteers working towards a common goal.

Challenges in this early stage had to do with group formation and choosing which problem would be most fruitful and exciting to work on. Responding to feedback, refining the problems, narrowing the scope of the project, and being persistent in pitching from week to week were critical to building a dedicated and focused team.

The Project's Journey

Timeline of our project; Visual by Kenny

Backend Data Work Timeframe: March to August

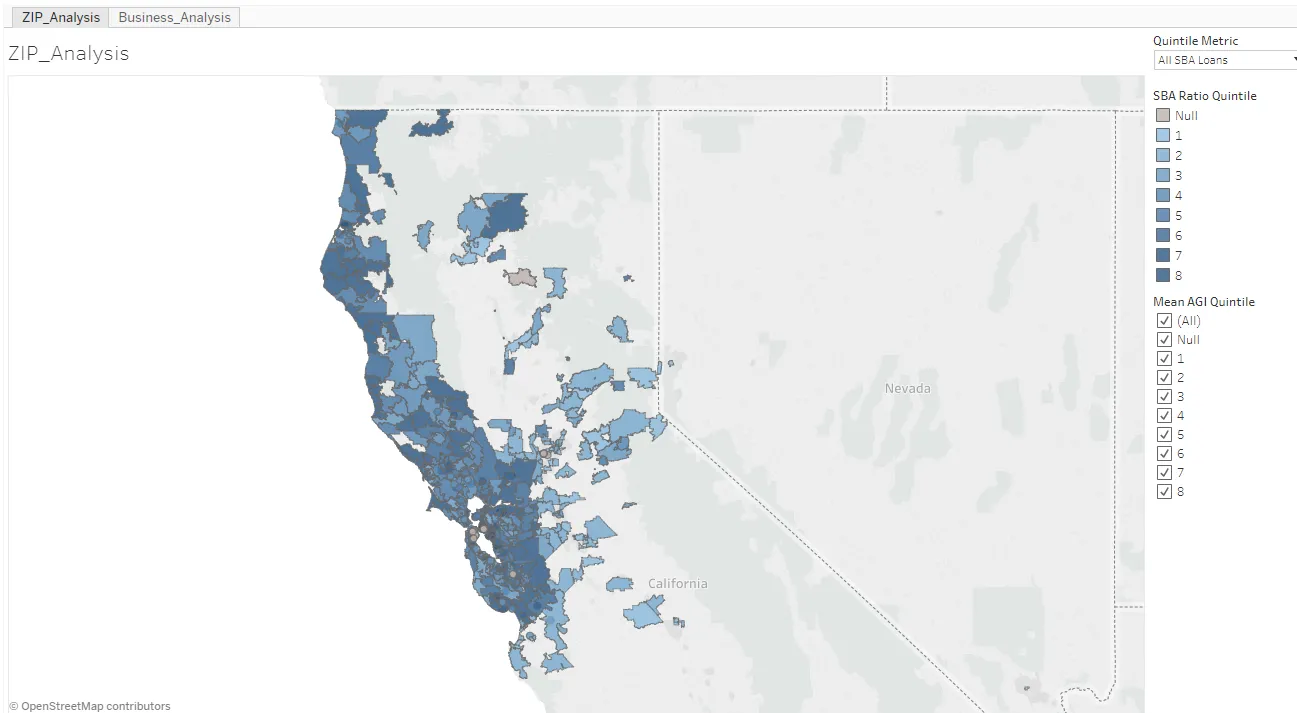

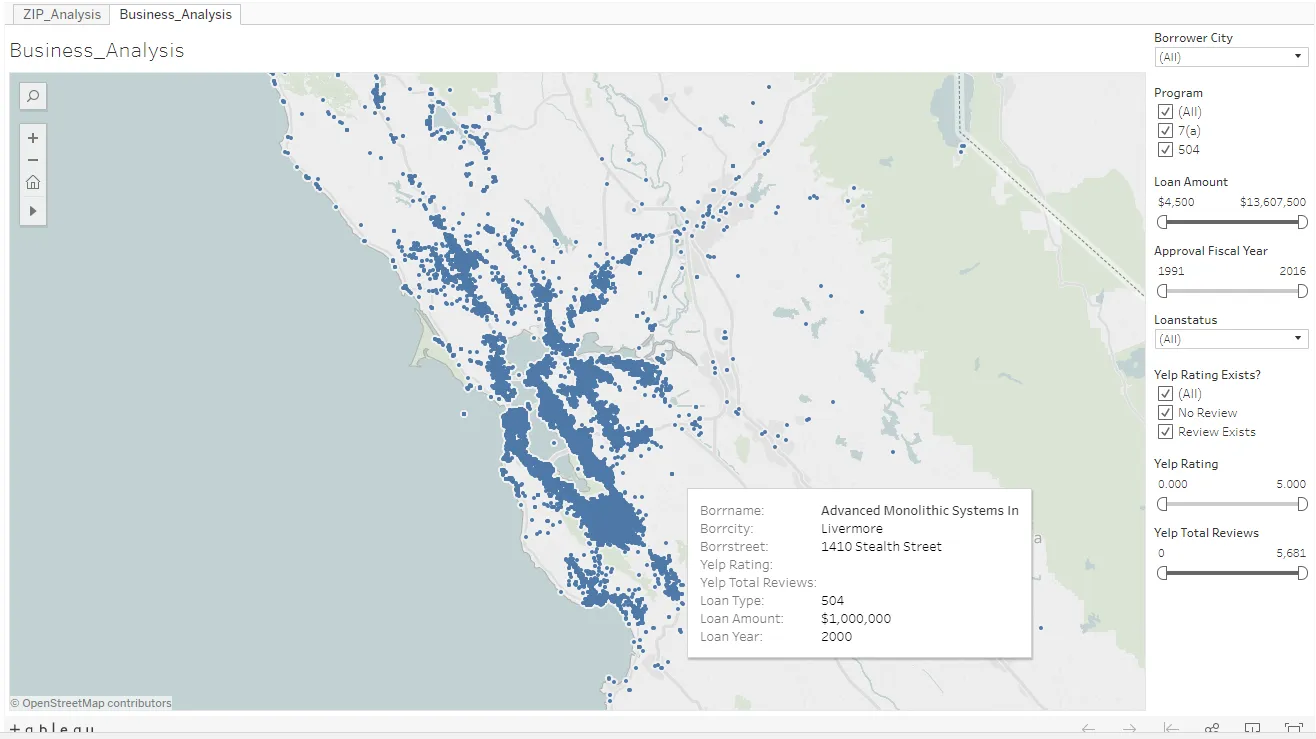

As the team began to gel in March, Noah worked with new members who came in each week to understand what data was publicly accessible and onboard them into the project. The technical team also investigated and downloaded data from additional public sources such as the US Census. There was enough data available to commit to working on an analysis of participation levels (the second problem statement). We began to envision a web app that would show information by county or zip code and later investigated whether we could map by congressional districts as well using the same data. An early prototype in Tableau came together quickly and was used to refine what we wanted in later, more polished iterations of a final prototype.

Vince La took charge of tracking the ideas and requests that would arise each week. Each weekly hack night consisted of huddles to talk through tough problems followed by doling out assignments to complete before the next meeting.

By mid-summer, the group had a solid pipeline that would pull the data from the SBA website, combine it into a single hosted database, and then connect the business data to third-party APIs from yelp and google to identify popular businesses. We also started to explore the next iteration of visualizations at this time.

Challenges in this stage included what database software to use, what front end and hosting services to use, as well as a lack of knowledge of some of the latest visualization technologies. Some third party services exist, but require a key to use or have limits on the number of queries per period. There are some opportunities for the larger brigade organization to establish vendor relationships to allow work to proceed without incurring large costs or flow limitations.

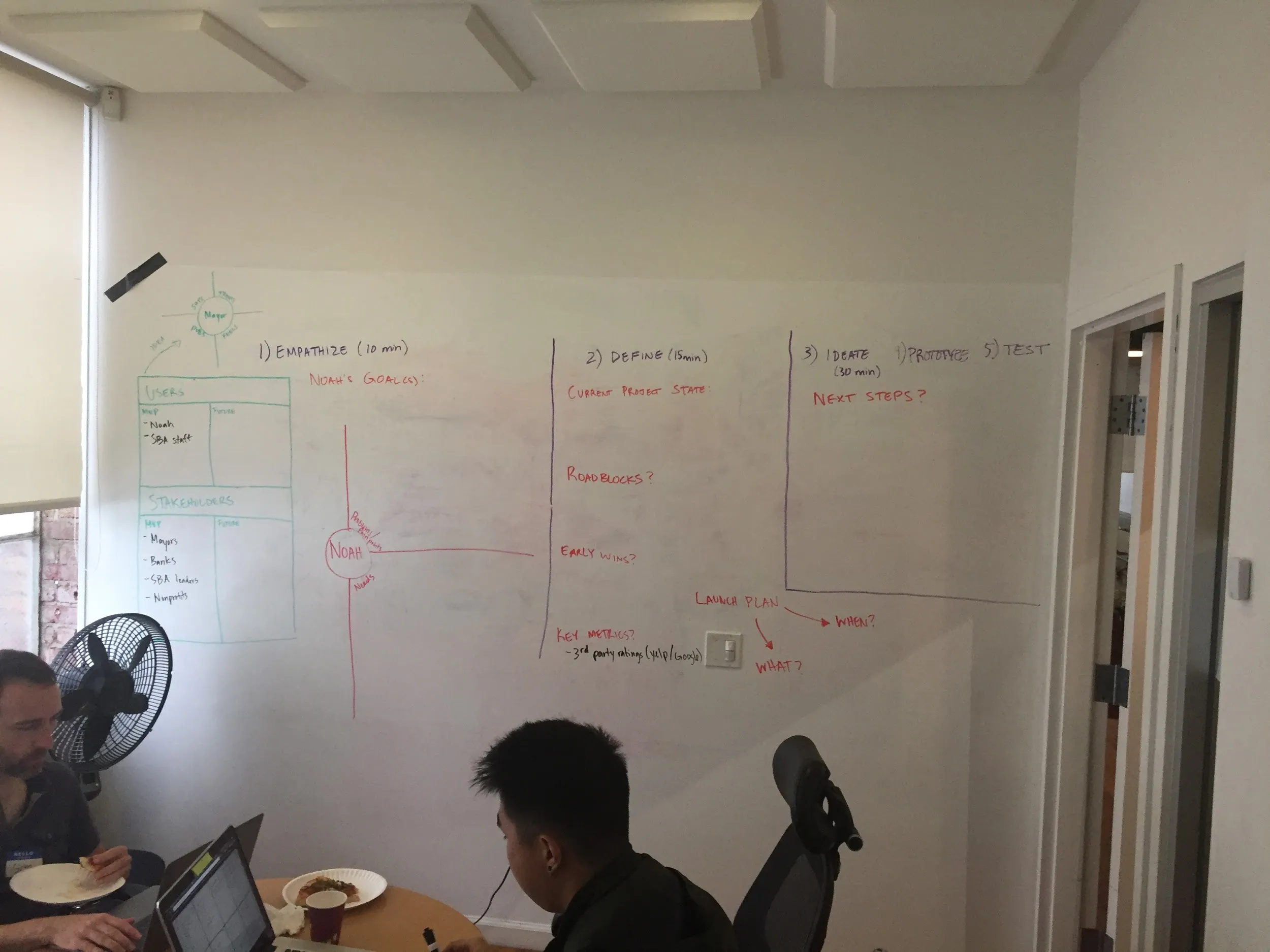

Phase 3: Defining the MVP and gaining Momentum Timeframe: August to September

In this time period, a few key moments occurred that pushed the project’s momentum forward:

- We formed a front-end development team and a UX design team

- We hosted a design sprint that defined a concrete MVP

- We set a deadline to present our MVP to SBA’s digital team

In the months prior, a lot of the key data engineering was completed. We were fortunate to have new volunteers join that happened to cover the needs of the team, i.e. designing and developing the medium that would share all the data work.

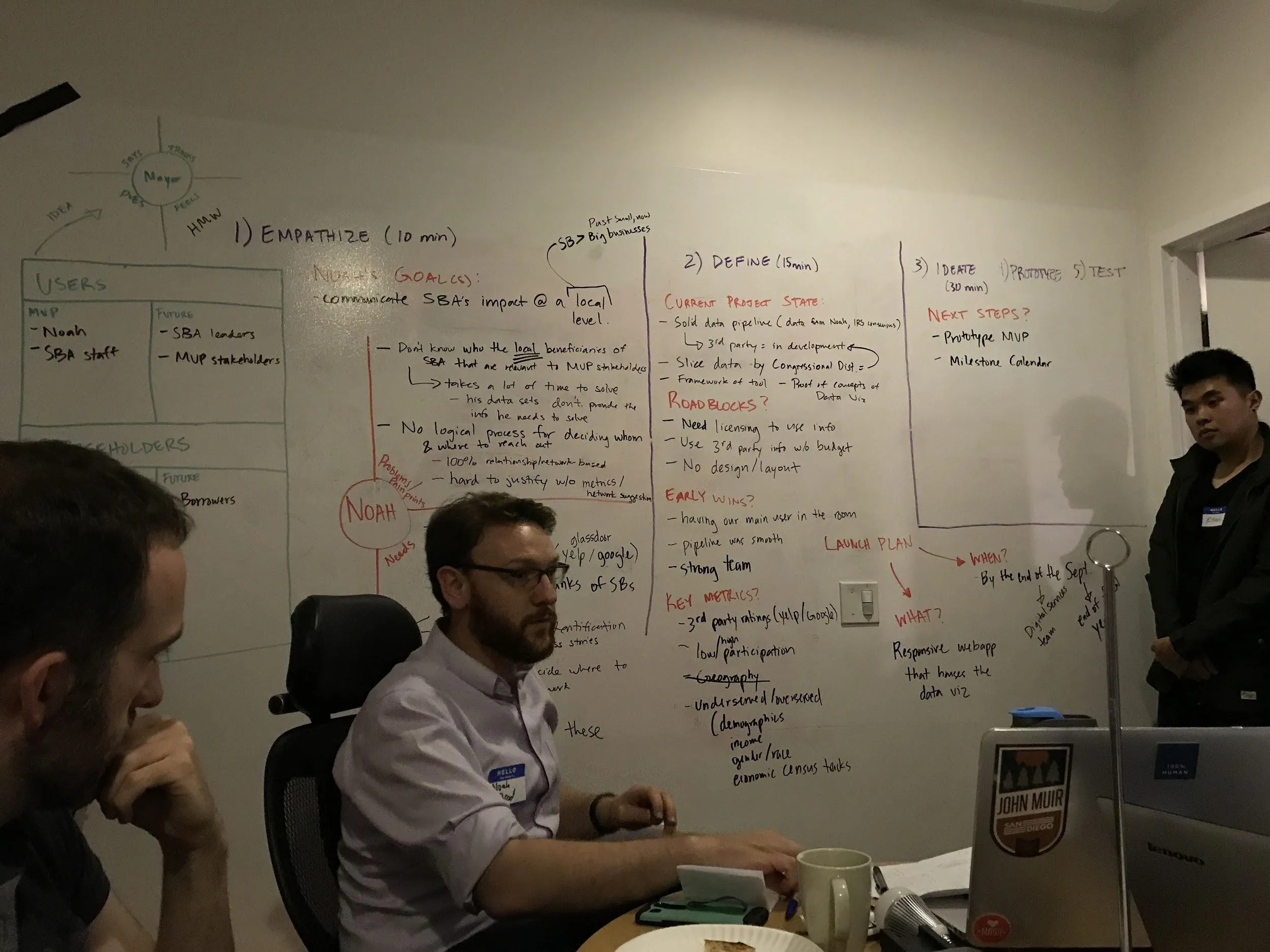

The sprint we hosted was based on Google’s sprint practice. Typically, the sprint takes place for a few full days, back-to-back. This wasn’t a realistic timeline for us since we only meet one night a week for a few hours. For our needs, group member Kenny Nieh created a condensed version of the sprint that focused on understanding the user’s problems and needs, defining the MVP’s scope and requirements, and ideating features out of all of this. By the end of the white board session, we set a deadline and timeline to complete the MVP prototype within 3 weeks and defined the 3 key key things our users would need to get out of the MVP:

- A high-level understanding of SBA’s economic impact on small businesses

- References to successful SBA-support small businesses

- Identification of which small businesses are support by SBA

The Whiteboard, pre-sprint

The Whiteboard, pre-sprint

Post-sprint

Post-sprint

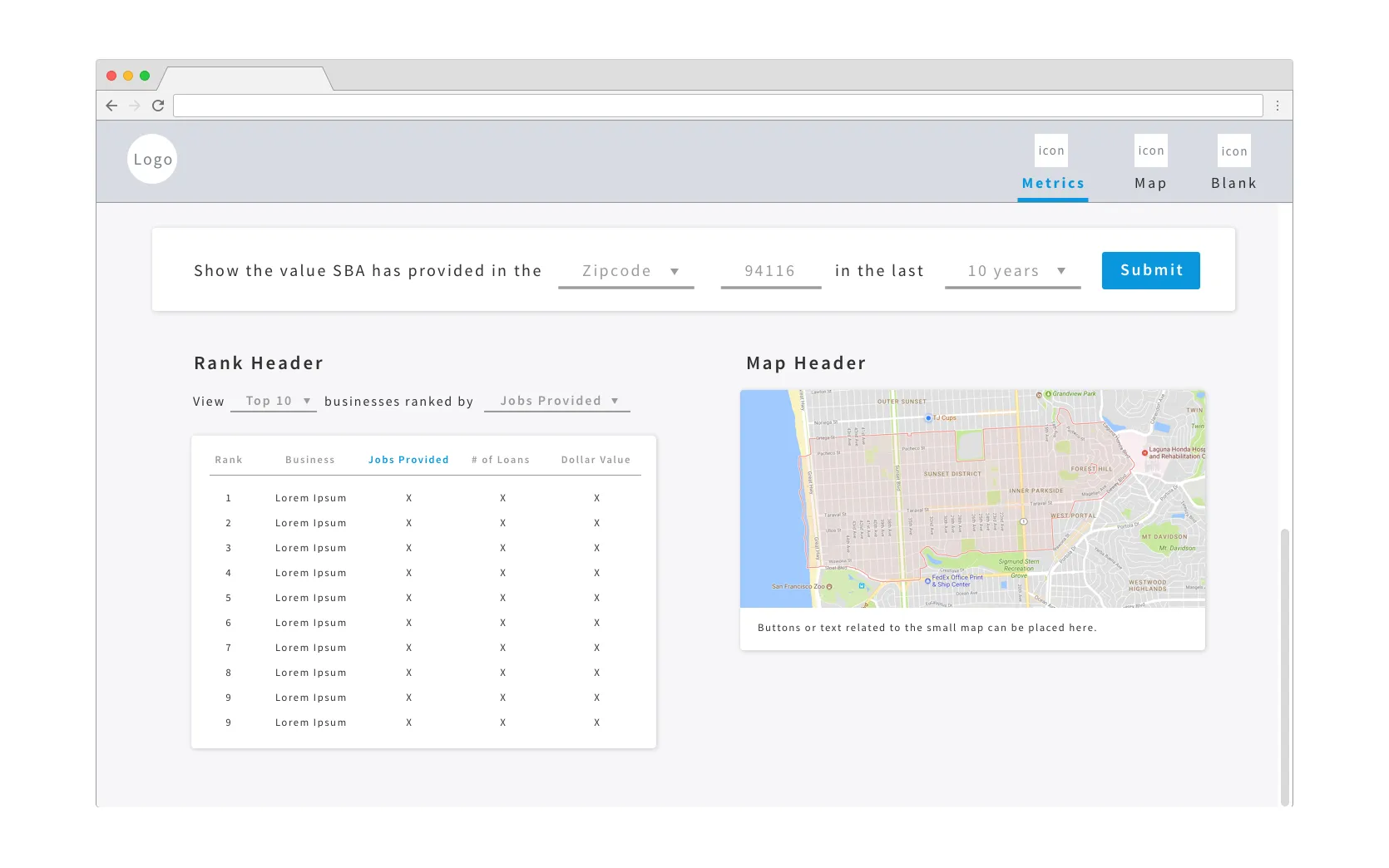

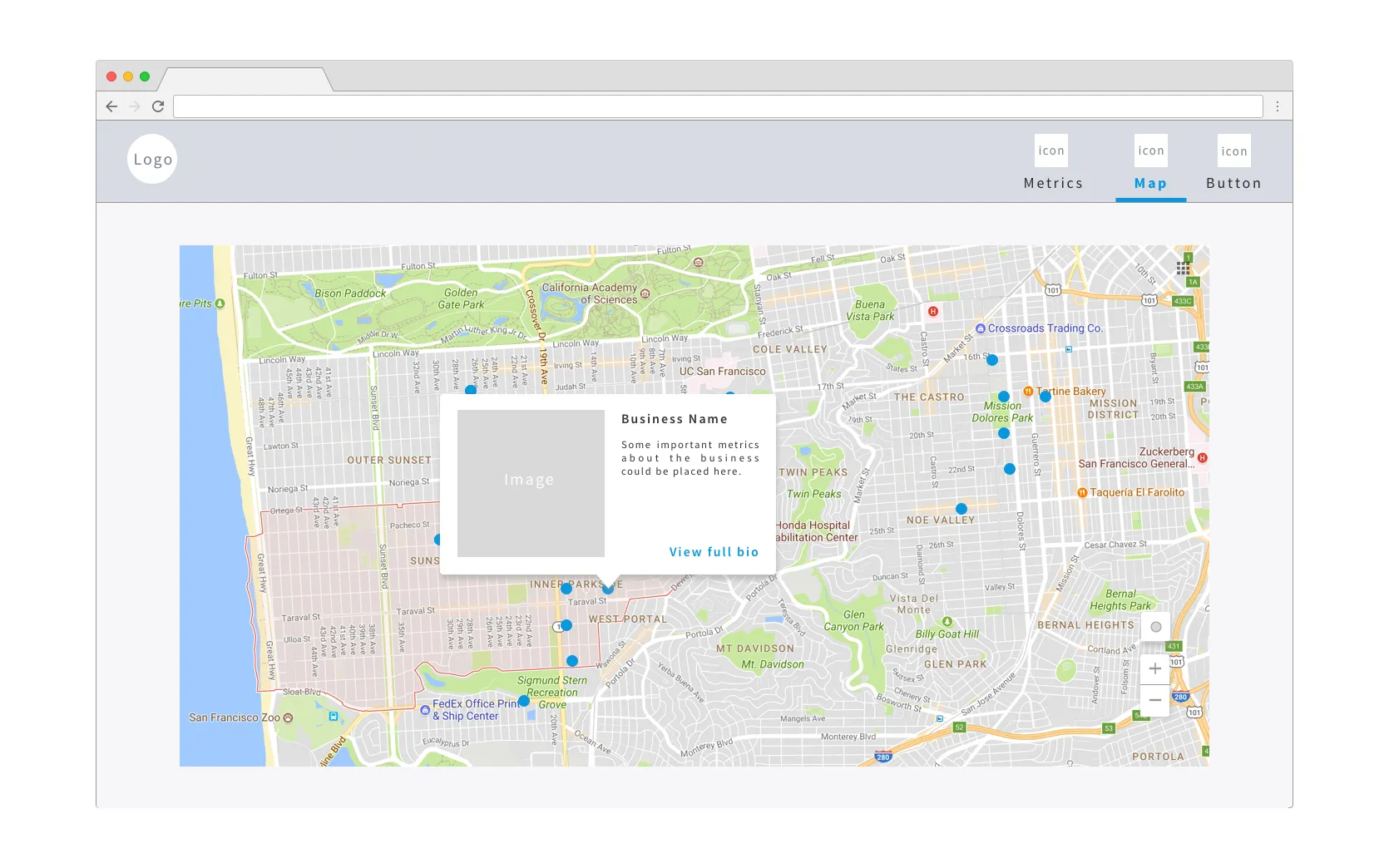

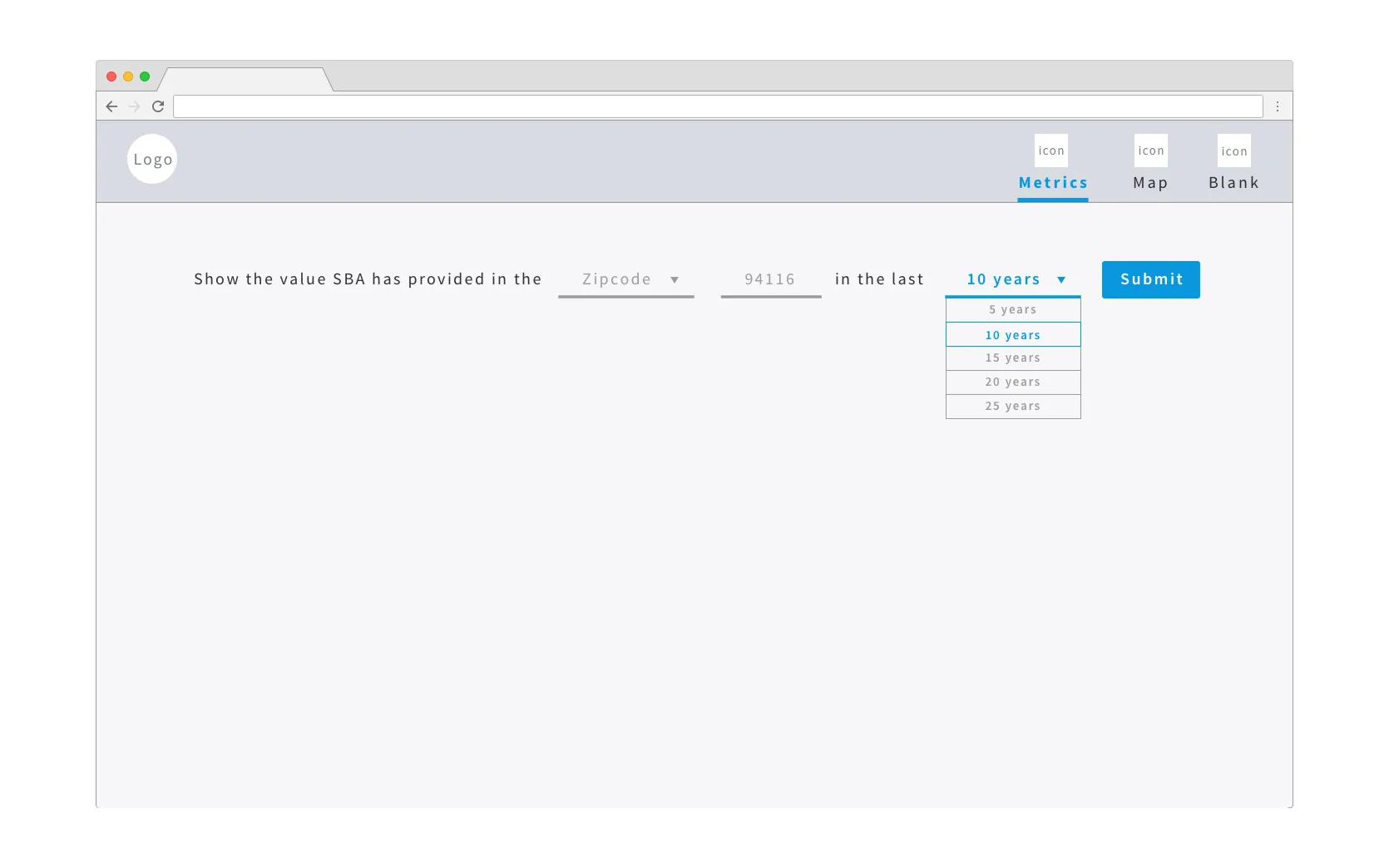

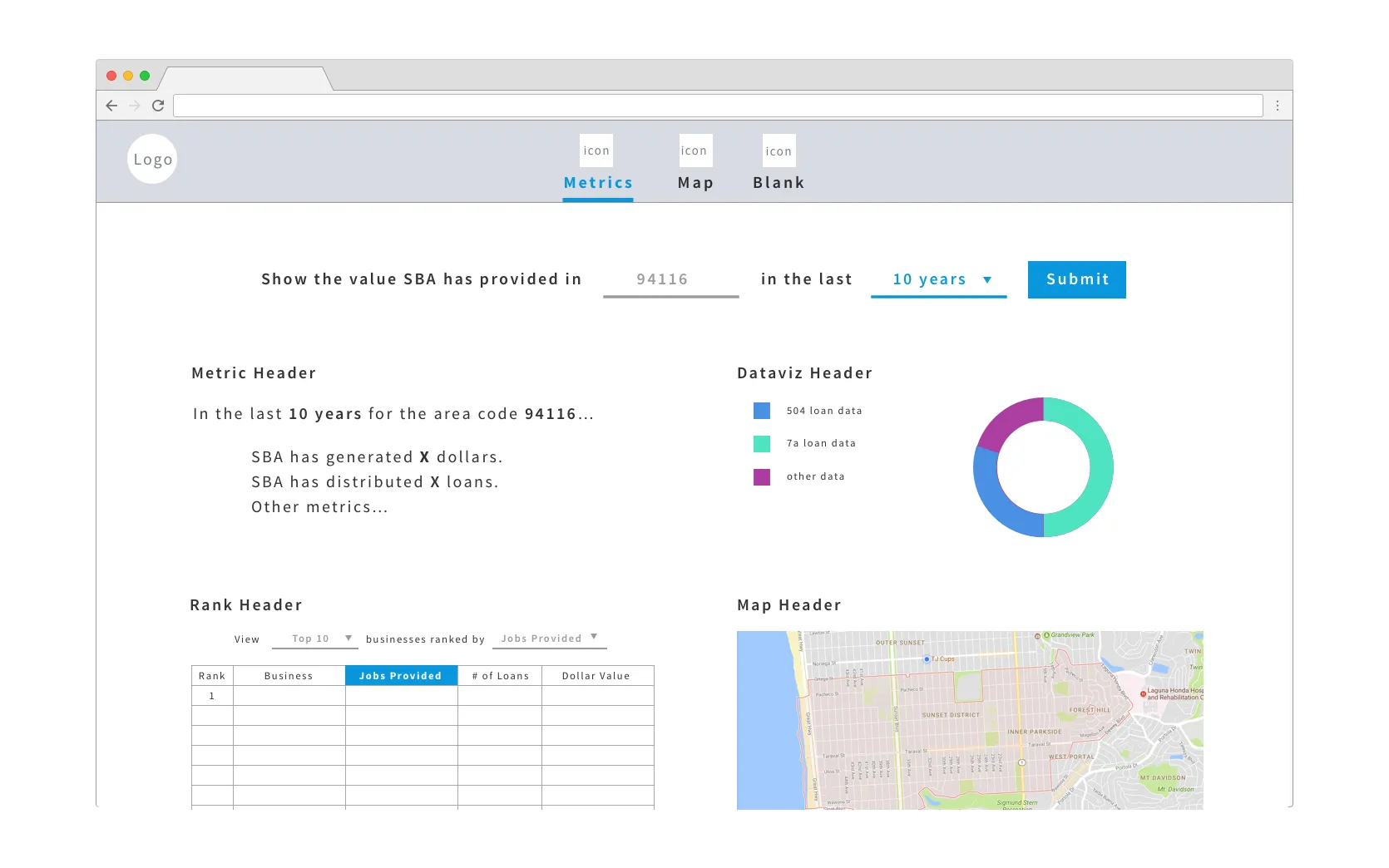

Moving forward, the design and development team met a few times to define technical constraints and distill our sprint findings into specs and features. Given a tight timeline of 3 weeks, we pulled together some wireframes and coded them out.

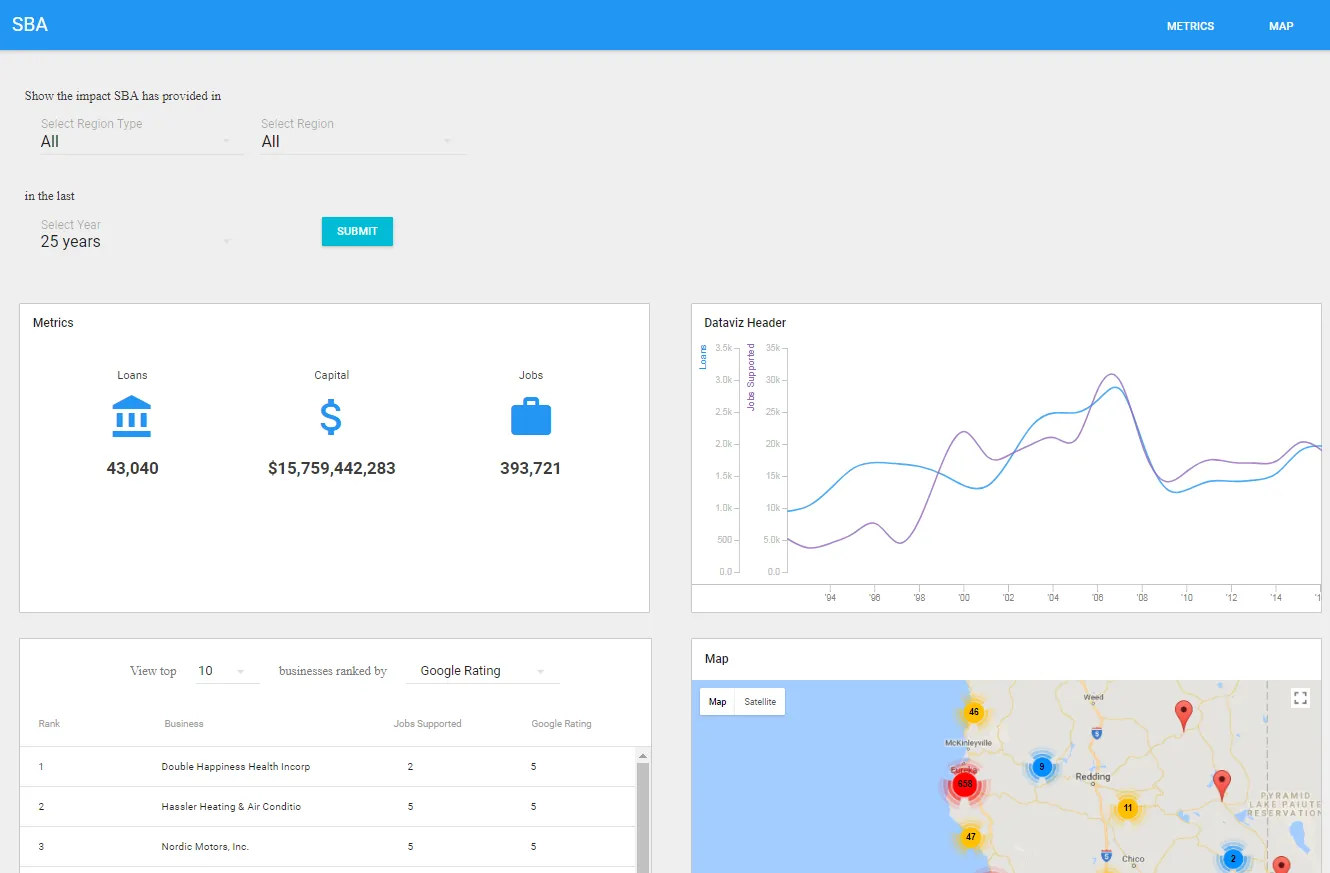

There are 4 main components to it:

- Form fields that allow you to select a location and time range to search data by

- High level metrics showcasing SBA’s impact

- A ranking of top local businesses

- A map-based data visualization of SBA’s impact, including tool tips for local small businesses

You can view our low-fidelity prototype here:

https://ec2-54-175-133-20.compute-1.amazonaws.com/app/

Phase 4: MVP Push Timeframe: September to Present

Working under a tight deadline, the SBA data science group came together and synthesized the past 10 months of research, testing, and development to creating an low-fidelity interactive prototype in time for Noah’s meeting with SBA stakeholders. Noah’s meeting was held at the end of September and provided an opportunity for him to share the SBA loan analysis tool and to discuss the future of this tool. Topics such as feasibility, scalability, development, and SBA data science group’s future involvement was discussed.

Success metrics for this project

The SBA data science group established a set of success metrics or KPI’s for the loan analysis tool:

- At minimum it is desired that the discussion surrounding the SBA loan data would open up a discussion within SBA to make their open data more easily digestible and accessible. The SFbridage’s prototype provides proof of concept of what can be done with open data and how the SBA itself can benefit from making their data more open.

- A minor win for the SBA data science group would be that the SBA loan analysis tool be adopted by SBA itself, further developed, and tested and utilized locally in the San Francisco office as a pilot.

- A major win for both the SBA data science group would be that the SBA loan analysis tool becomes an internal or external tool used nationally through-out SBA offices. Scaling the SBA loan analysis tool for national usage in other SBA districts could set an example for the possibilities of what can be done with other open datasets.

The SBA data science group is a volunteer group that has met weekly for the past 10 months. The group is comprised of data scientists, developers, engineers, UX designers, and the client.

Major Takeaways

SBA: Working with Civic Volunteers - Noah Brod

For me this project was an excellent example of how government agency employees can productively engage with the civic tech community to develop small pilots that address very local needs and demands. Rather than expecting solutions to come out of a long process at a national level all at once, local solutions can be designed rapidly and developed by regional and field offices, which can then be piloted and possibly gain national adoption based off of those pilots. This entire process can generate very interesting products and solutions at a very low cost from an agency perspective. The added benefit is that a small pilot can easily generate dozens of spin-off projects and ideas as the observations and questions raised by the pilot emerge. For instance, this project drove a number of spin-off conversations around improving how SBA releases its data generally, in what format, and in what condition.

Leading and Forming a Data Science Team - Vincent La

The value of civic tech is not in complex analysis or code but the product that is delivered to its end user and how it helps them solve their problems. The biggest lesson I learned from this is that the most valuable resource to ensure a successful project is an engaged civic partner who is actively facing challenges in their community — in this case Noah. Having Noah guide us each week to set scope really helped keep the tech team on track and focused towards providing meaningful solutions.

In terms of leading a data science team, I found that the most important thing was creating a process-driven approach to emphasize documentation, data quality, and infrastructure. When I first joined this project, every week resulted in ad-hoc work and it was hard to build on each other’s work week-to-week. Especially given that this is an all-volunteer group, the first problem to solve is “key-person” risk. You may not necessarily know if the person who was working on a model or on some code one week will be back the next week. Being aware of the following points will help increase the chances of success:

- You may need to refill roles as people are constantly coming and going.

- You may need to recruit additional skills as you explore ideas.

- You should have at least one person in charge of onboarding team members every week. This person can change each week.

- Look ahead of product timeline and think what roles you’ll need coming up. Start pitching for them early.

- Pitch for very specific skills to gain better chances of pulling in the right people.

In terms of tooling and infrastructure, it’s important to minimize workflows that results in outputs being stored locally. With small teams or with prototyping, it’s perfectly fine to manipulate some Excel sheets locally or load up a CSV in a Jupyter notebook and create some visualizations. The problem with scaling this, especially in an all volunteer group, is that is becomes immediately unclear which work is necessary for production and driving towards the final “product”, and which was just exploring and now unnecessary. Our first biggest win on this front was getting a PostgreSQL database hosted on Microsoft Azure, thanks to their continued and generous support of Code for San Francisco. With a database hosted in the cloud that anyone could access it became much easier to build on each other’s work and know what the most current state of our data is. However, even with a database, we still needed a process to keep everything documented and organized. For this, we created a “data pipeline”, a process through which we extracted, loaded, and transformed data in our database. You can create a pipeline in many different ways; for us it was a series of SQL and Python scripts that ran in a defined chronological order. Furthermore, we (at least tried) to abide by two guiding principles

- The database at any time should be reproducible by everything in the Extract-Transform-Load (ETL) code. That is, if anything gets accidentally dropped or mis-transformed, the entire database could be recreated by simply re-running the data pipeline from start to finish.

- Everything in the database can be traced back to code documented and version controlled (we used Git/GitHub).

Our second big win in terms of tooling was a shared online SQL editor and analytics platform, generously donated to us by Mode Analytics. By connecting our database to Mode Analytics, anyone with SQL knowledge could query our database without having to download any files and in a friendlier UI.

Finally, note that a lot of the above did not have a direct tie to data science, and reflecting back, even with data science projects, especially in an all-volunteer group, the biggest reasons for success are good documentation, establish process-driven approaches, and infrastructure to maintain and share data. I learned a lot from working cross-functionally and always keeping a focus on the product.

What was a big win for you or a major learning point?

“I found it very energizing to be surrounded by a group of smart volunteers with such a diverse set of skills.” — Mike Mathews, Data Pipeline Engineer

“A major win for me was showing what could be done simply by engaging with the open source and civic tech communities directly - opening the doors to a motivated and talented community of volunteers created benefits for our agency, the volunteers themselves, and public as well.” — Noah Brod, Project Sponsor

“The collaborative approach and inclusive nature of the volunteers made for an extremely positive project experience. The major win for me was how transparent everyone was when communicating about challenges, feasibility, expectations, and schedule changes.” — Brianna Bischofberger, UX Designer

“Coming from a UX design background, this project was a breath of fresh air! I love how the user we were designing for (Noah) was an active part of our product development - showing up to our weekly meetings and participating in our slack group. It made keeping the product user-centered so much easier.” — Kenny Nieh, Product Designer